Image: Nathan Reading (CC), Flickr

The World Health Organization has released a significant report marking what I think must be the first attempt to quantify antibiotic resistance globally. It’s a very sobering read — not just for what the data says about the advance of resistance worldwide, but also because of what the organization could not say, because the data doesn’t exist.

The numbers themselves are unsettling. Dr. Keiji Fukuda, the WHO’s assistant director general, told the press: “It’s clear that rates are very high of resistance among bacteria causing many of the most common serious infections – the ones that we see both occurring in the community as well as in hospitals … In all regions of the world, we now see that hospitals are reporting untreatable, or nearly untreatable, infections.”

But the gaps in the numbers are too: There are 194 member countries in the WHO, but only 114 had the data-gathering resources to contribute something to the report, and only 22 were able to send in data on the most important occurrences of resistance in very common bacteria. Thus it’s possible that the report could be an under-estimate, or an over-estimate. But I can’t think of a scenario in which it could be considered substantially inaccurate. Its portrait of a world in which antibiotic resistance is advancing to grave proportions ought to be taken seriously.

Here are some snapshots of the data the report gathers, sorted by the six regions into which the WHO divides the world:

E. coli (causes urinary tract infections, sepsis in newborns) resistant to 3rd-generation cephalosporins: up to 70 percent of bacterial samples in Africa, 48 percent in the Americas, 63 percent in the Eastern Mediterranean, 82 percent in Europe, 68 percent in Southeast Asia, 77 percent in the Western Pacific.

Klebsiella (causes hospital outbreaks) resistant to carbapenems, one of the last remaining last-resort drugs: 4 percent of bacterial samples in Africa, 11 percent in the Americas, 54 percent in the Eastern Mediterranean, 68 percent in Europe, 8 percent in Southeast Asia, 8 percent in the Western Pacific.

Staph (skin infections, hospital infections, pneumonia) resistant to beta-lactam drugs, that is, turning into MRSA: up to 80 percent of bacterial samples in Africa, 90 percent in the Americas, 53 percent in the Eastern Mediterranean, 60 percent in Europe, 26 percent in Southeast Asia, 84 percent in the Western Pacific.

Gonorrhea with diminished susceptibility to 3rd-generation cephalosporins, about which the WHO says “There is no ideal alternative… there are very few new treatment options in the pipeline”: up to 12 percent of bacterial samples in Africa, 31 percent in the Americas, 12 percent in the Eastern Mediterranean, 36 percent in Europe, 5 percent in Southeast Asia, 31 percent in the Western Pacific. Cases of untreatable gonorrhea — which causes serious infections in newborns, and also infertility — have been found in 10 countries so far.

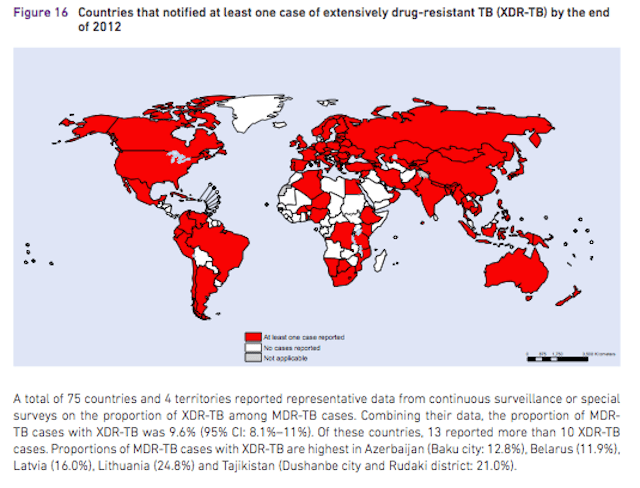

In some cases the report’s graphics make a better case for the seriousness of the problem than the numbers do. Here for instance is the map of the 92 countries which have reported at least one cause of effectively untreatable XDR-TB. That’s a lot of red.

from WHO, original here

The WHO used the launch of the report to make a plea for nations to begin doing a better job of tracking resistance within their borders and sharing information across them, which is critically important (and something that some researchers, such as Dr. Timothy Walsh, the co-discoverer of NDM, has been pressing for a while).

In case all this seems just numbers-heavy and wonkish, it’s worth considering what Fukuda stressed while releasing the report (and, FWIW, what I argued in Medium last year): rates of resistance this high bring us close to a post-antibiotic era. He said:

When people develop cancer and are on chemotherapy and become immunocompromised, they are at much higher risk for complications and infections and severe ones. When babies are born prematurely, they are in the same situation. When we have children who are malnourished, they are at much higher risk for infections. When we have people coming in for surgery — it may be elective surgery such as getting joints replaced or heart surgery or it may be as the result of car accidents or wounds and things like that, but again we depend on antimicrobial drugs to help people to get through those things and when we have people with common illnesses like severe diabetes or are on dialysis from renal failure — again, these people are at much higher risk for infections and we rely upon these medicines to protect them.

That is what it means when we say that it really begins to get at our ability to protect people when they are most vulnerable… We should expect to see that there are going to be some people who simply have untreatable infections. We can’t do things about them.

Homepage Image: Samantha Celera