Live-poultry market, Shandong, China, 2009. Jonas_in-China, Flickr

Cast your mind back to about this time a year ago. A novel strain of flu, influenza A (H7N9), had emerged in China, in the provinces around Shanghai. International health authorities were deeply concerned, because any new strain of flu bears careful watching — and also because, on the 10th anniversary of the SARS epidemic, no one knew how candid China would be about its cases.

By the time peak season for flu ended in China, there had been 132 cases and 37 deaths from that newest flu strain. But, confounding expectations, the Chinese government was notably open about the new disease’s occurrence, and scientists worldwide were able to ramp up to study it. Still, no one could say whether that flu would be the one to make the always-feared leap to a pandemic strain that might sweep the globe. As with other, earlier, worrisome strains of flu, science could only wait and see whether it might return.

And now it has.

In the wake of Lunar New Year, and the enormous internal migration it triggers as people return home for celebrations, China has been reporting a steady flow of new cases of H7N9: seven one day, 10 on another, 14 on the day after that. This morning, the World Health Organization announced that the Chinese government notified it over the weekend of 15 new cases, including one death. Simultaneously, Xinhua News reported a case of H7N9 entering mainland China: a 6-year-old boy who crossed from Hong Kong.

The current case count is very hard to pin down. (In a story 10 days ago, expert flu reporter Helen Branswell presciently remarked: “The numbers are rising so fast it’s tough to keep track of where the count stands. Between the time this article is written and when it is read, the numbers will almost certainly change.”)

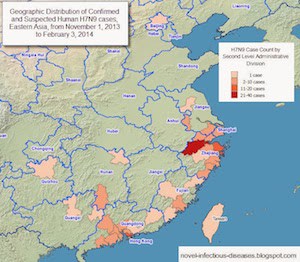

original: novel-infectious-diseases.blogspot.com

The WHO does not add cases to its tally until they have been lab-confirmed and acknowledged by China’s Ministry of Health, so the totals it reports, while thoroughly vetted, lag behind probable cases by days or weeks. The most rapid, but not lab-confirmed, count is compiled by the community of flu geeks collectively known as FluTrackers, and is crowdsourced from translations of Chinese-language media. Their current tally stands at 336 cases since H7N9 first surfaced.

That total is an important number, for two reasons. First, because the number of cases in the “second wave” of H7N9 (from late autumn 2013 until now) exceeds those in the first wave of outbreaks. And second, because it suggests that H7N9 is managing more rapid spread than the flu strain that has been the subject of the greatest international concern, avian flu H5N1: 336 in 12 months, versus 650 in 10 years.

So far, according to the WHO, almost all of those who have fallen sick have had some contact with individual live poultry, or visited a live market where poultry are slaughtered on site. That’s consistent, not just with the known risks of H7N9 and other avian flu strains such as H5N1, but also with the lunar holiday. Poultry is a culturally significant dish for New Year festivities, and buying the bird live and having it killed remains an important part of the process. Across Asia, persuading people to buy supermarket-style dead, cut-up chicken has been difficult just for normal family meals, and more difficult for holiday ones. And even when live-market closings have been ordered, the mandates are not always followed. (See this 2010 PLoSOne paper for a network analysis of live-poultry sales and the spread of H5N1.)

Last week, the New England Journal of Medicine published a lengthy analysis of H7N9 cases across 2013 by Chinese authors (from the national Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Beijing, and the Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention). From their abstract (though the whole article is available), their round-up of the cases:

Among 139 persons with confirmed H7N9 virus infection, the median age was 61 years (range, 2 to 91), 71% were male, and 73% were urban residents. Confirmed cases occurred in 12 areas of China. Nine persons were poultry workers, and of 131 persons with available data, 82% had a history of exposure to live animals, including chickens (82%). A total of 137 persons (99%) were hospitalized, 125 (90%) had pneumonia or respiratory failure, and 65 of 103 with available data (63%) were admitted to an intensive care unit. A total of 47 persons (34%) died in the hospital after a median duration of illness of 21 days, 88 were discharged from the hospital, and 2 remain hospitalized in critical condition; 2 patients were not admitted to a hospital. In four family clusters, human-to- human transmission of H7N9 virus could not be ruled out. Excluding secondary cases in clusters, 2675 close contacts of case patients completed the monitoring period; respiratory symptoms developed in 28 of them (1%); all tested negative for H7N9 virus.

So what next? With flu, no one can ever know what will happen until it does — though anyone with any background in flu assumes that something big will happen, sooner or later, with one emergent strain or another. If you are inclined to keep track, here are some key sources:

FluTrackers’ H7N9 forum is here (also in French, Spanish, Italian and Dutch).

My former colleagues at CIDRAP (the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy) are doing day-to-day granular reporting with links to CDC and WHO documents and news sources.

Helen Branswell works for a wire service, meaning that her stories appear in many outlets. The quickest way to see her new articles may be to follow her on Twitter.

The lead bloggers on this topic are unquestionably Crawford Killian at H5N1 and Mike Coston at Avian Flu Diary (and unlike CIDRAP, they publish on weekends. And nights, and holidays.). Australian academic Ian Mackay, PhD has been providing great context at Virology Down Under, and infectious-disease physician Judy Stone, MD of Molecules to Medicine recently contributed a deep primer on flu strain terminology.

(NB: Whenever I write a round-up of flu-news sources, I inevitably miss someone important. Apologies in advance if I did, and feel free to add recommendations in the comments.)