Plates of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) in CDC’s healthcare-associated infections laboratory.  Center for Disease Control/AP

Center for Disease Control/AP

The government-chartered British project examining antibiotic resistance — which made such a splash in December with its prediction that untreatable resistance will kill 10 million people per year by 2050 — has produced its first set of recommendations for turning back the problem.

They come down to this: Start spending money.

The project — formally titled the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance — analyzes the funding spent directly on resistance research, and indirectly through training specialists and investing in innovation, and finds that the resources devoted by governments and the private sector are not up to the job. With the same bluntness that marked its first report, the project says: “There is a problem of chronic under-investment in both the financial and human capital needed to tackle antimicrobial resistance.”

The report, which went live this morning, is the second in a series that began in December and will continue until mid-2016. The Review was commissioned by UK Prime Minister David Cameron last summer, a follow-up to the dire report issued in 2013 by the UK’s Chief Medical Officer, which ranked resistance as serious a threat to society as terrorism. It is led by Jim O’Neill, previously the head of economic research for Goldman Sachs, and supported by the nonprofit Wellcome Trust. Its first report attempted to define the size of the resistance problem, using research conducted by the consulting firms RAND and KPMG. It estimated that resistance currently accounts for an estimated 50,000 deaths in the US and Europe, and 700,000 worldwide. And it predicted that if resistance cannot be curbed, deaths per year will balloon to 10 million by 2050, and cost the world up to 3.5 percent of its total gross domestic product, $100 trillion.

This second report begins to work on solutions. Its recommendations, briefly:

- Invest in basic science research.

- Find ways to use existing antibiotics for longer, by combining them with other drugs or changing doses.

- Improve diagnostic technology, aiming for tests that can deliver information about an infection very rapidly in a medical office or by a hospital bed.

- Train a new generation of specialists to tackle the problem.

- Extend and modernize surveillance for resistant organisms.

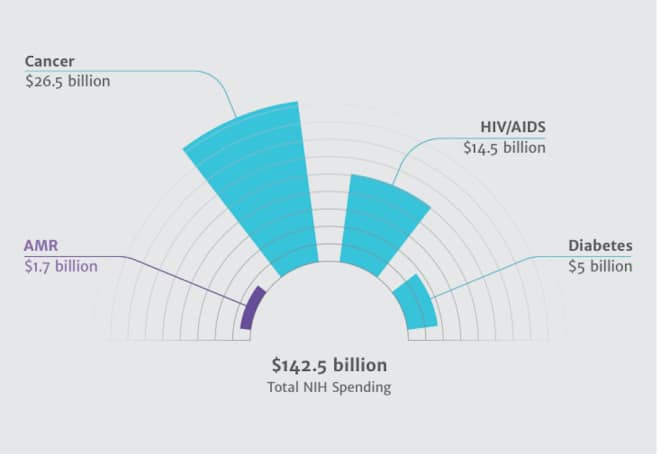

One real surprise in the report: the results of an analysis of US and European federal spending on resistance. The National Institutes of Health, the world’s largest single funder of medical R&D, spends only 1.2 percent of its research budget on resistance. The situation in Europe is just as dire: 1.8 percent of all medical research.

The report backs up that analysis with a look at the private sector’s response to resistance, and again finds a lack of investment. Of the top 25 indications — disease states for which a drug would be used — for which there are products in development, 22 are for chronic conditions and non-communicable diseases (cancer, for instance, or heart disease). The other three are infectious, but not core resistance problems: HIV, hepatitis C and flu. There are currently 67,000 registered clinical trials for products addressing non-communicable diseases; 23,000 for infectious diseases, mostly HIV, TB and malaria; and for bacterial infections that are or could become resistant, just 182.

Possibly the most dismaying finding is that the corps of people who would treat and research resistance is underfunded and shrinking. In the US, the report says, HIV and infectious disease physicians are the lowest-paid among the top 25 medical specialties, and the highest-ranked specialty journals are not considered prestige platforms to publish on. This especially made my jaw drop: Medical students don’t aspire to be infectious disease physicians any longer. For every 100 residency slots in neurology, there are 250 applications; for every 100 plastic surgery slots, 200 applicants. For every 100 infectious-disease slots, there are only 84 students who want to train.

Applicants per vacancy for US medical residency programs.  courtesy the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance.

courtesy the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance.

The top recommendations, out of many in this report:

- Create a “global innovation fund” to support early-stage research, open to academic, public health and industry scientists.

- Explore new regimens for the remaining antibiotics that still work, modeled on the energy industry’s attempts to use existing power sources more efficiently while looking for new ones.

- Aim for achieving new diagnostic techniques and tools, and also for training personnel in health care to use them.

- Raise the prestige of infectious disease research, perhaps by creating international “centers of excellence” that share research programs.

- Increase resistance surveillance internationally and use big data techniques to extract the maximum value from the information being collected.

The report ends with a reminder that, as large as the investments they call for might be, the cost of not attending to resistane will be higher:

A solution to antimicrobial resistance need not be expensive. It is likely to cost the world much less than 0.1 percent of global GDP. Weighed against the alternative — $100 trillion in lost production by 2050 and 10 million lives lost every year — it is clearly one of the wisest investments we could make.