Photo: Ishai Parasol/Flickr

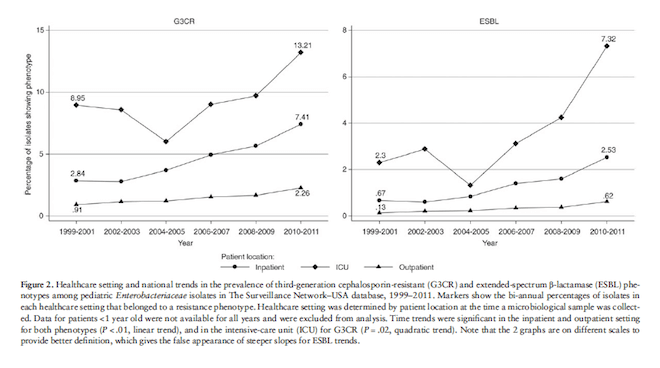

Here’s some disturbing news published late last week in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society by a team of researchers from two Chicago medical institutions plus an expert analyst of antibiotic resistance: Serious drug-resistant infections in children are rising across the United States. While the rate of their occurrence remains low overall, they nonetheless increased two- to three-fold over 10 years.

The group plumbed a national database of disease-causing bacteria retrieved from child patients who were treated in intensive-care units, regular hospital wards, and outpatient clinics between the beginning of 1999 and the end of 2011, looking for a particular pattern of resistance. That pattern, known as ESBL for short (for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase), indicates that bacteria no longer respond to a wide array of common antibiotics: any chemical relative of penicillin, and any of the cephalosporins. Bacteria that are ESBL-resistant respond to only a few remaining big-gun drugs, notably a small family of drugs — already under pressure from other resistance factors — known as the carbapenems. ESBL resistance is a particular concern because it tends to occur in gut bacteria such as E. coli; bacteria that have picked up that resistance DNA can be carried around undetected in the intestines and then cause a surprise infection later. Plus, some of that resistance DNA resides on plasmids, small loops of genetic code that transfer easily from one bacterium to another.

Here’s what the researchers found, looking at 368,398 bacterial isolates from child patients:

- Among the bacteria collected in 1999-2001, ESBL resistance was present in 1.39 percent.

- In the same period, resistance to third-generation cephalosporins was 0.28 percent.

- In 2010-11, ESBL resistance rose to 3 percent and third-generation cephalosporin resistance to 0.92 percent.

The trends were consistent across all the places where children were treated: ICUs, regular hospital floors and outpatient clinics:

from Logan et al. 2014, p.4. original here.

And, troublingly, the resistance patterns the group noted didn’t stop at ESBL and third-generation cephalosporin resistance. They note:

The most common co-resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics in both groups was trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (G3CR 52.8% and ESBL 66.1%), followed by aminoglycosides (G3CR 45.9% and ESBL 64.5%), and fluoroquinolones (G3CR 32.8% and ESBL 54.3%). Although the majority of isolates tested carbapenem-susceptible (G3CR 96.5% and ESBL 94.2%), multidrug resistance was common, with 46.8% and 74.4% of G3CR and ESBL isolates testing nonsusceptible to 3 or more drug classes. (Emphasis mine.)

So, what does this mean? The first thing to note is that there isn’t all that much data on drug-resistant infections in children, so this is an important piece of news. A second point is that when drug resistance in children has been examined, the bacteria under study has more often been MRSA, drug-resistant staph, both its stubborn skin infections and also the virulent necrotizing penumonia that can kill a child in hours. So to have data about ESBL in children is new and important as well. The third, clearly, is that even though rates of ESBL in children are low, they are also rising — a trend that is also occurring in adults and that overall indicates that we are running out of the the antibiotic weapons we can direct against such infections.

But the really unnerving thing (though not new to anyone who has followed the ESBL story) is the high proportions of resistance that were found in children when they came to outpatient clinics: in 2010-11, 37.6 percent of the third-generation cephalosporin resistance and 48.8 percent of the ESBLs. The authors note that there is no way to know whether those children had previously been hospitalized, so it is possible they could have picked up those resistant bacteria inside a healthcare institution. But it is also possible that ESBL is spreading in children in the outside world. And that suggests that the problem of these difficult-to-treat bacteria is larger than anyone knows or can count.

Cite: Logan LK, Braykov NP, Weinstein RA, Laxminarayan R. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase–Producing and Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Children: Trends in the United States, 1999–2011. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 2014. DOI:10.1093/jpids/piu010. Online here, supplementary materials here.