If you do any kind of challenging travel — adventure travel, backpacking, even just going to less-developed parts of the world — you’ve probably evolved some sort of protective routine. You get shots, take your malaria medication, wash raw things before eating them and take a water filter for the bad places. (Please tell me you do this. Condoms, too.)

But a new study just published in EuroSurveillance, the peer-reviewed journal of Europe’s equivalent of the CDC, raises the possibility that even if you are doing the right thing, you could pick up some very nasty stuff while you’re abroad — and that what you bring back could endanger not only you, but others around you as well. A team of French researchers reports that healthy travelers who had no contact with foreign medical systems brought back extremely drug-resistant bacteria, probably just from drinking water, and that the bacteria persisted in their guts for at least two months after they came home.

In the past several years, travelers from South and Southeast Asia and the Balkans have returned to western Europe with infections caused by bacteria that picked up extra DNA conferring extreme drug resistance. Those resistance factors, which go by the initials OXA and NDM (and more generally by the category name CRE, which the US CDC’s director has called “nightmare bacteria,” or CPE), protect against the killing action of almost every drug in the medicine cabinet, leaving only one or two very old and toxic compounds as possible remedies.

Most of the people who have returned to the West carrying these highly resistant bacteria had the misfortune to be injured, or otherwise need medical care, while they were traveling. Since hospitals even in the industrialized world tend to be places where problematic infections lurk, that made sense. But from time to time, people manifested with these infections when they could not remember doing anything to expose themselves. The assumption was that they had forgotten the exposure. But, it turns out, maybe they hadn’t.

The French team asked 574 travelers going to sub-tropical areas to donate stool samples before they left and after they returned, to see what they had picked up during their time abroad. In three of them — all from the 57 out of the 574 who had gone to India — they found E. coli that was carrying this resistance-conferring DNA and that had not been present when the travelers left. From the paper:

Traveller 1 (C4-049)

A woman in her early fifties, had travelled alone as a backpacker and tourist to India for 17 days in April 2012. Upon return, she did not report any digestive disorders, any antibiotic intake or any contact with the local healthcare system during her travel. Investigation of stool samples revealed four phenotypically distinct Escherichia coli, including one that produced both a CTX-M group 1 and an OXA-181 carbapenemase. One month after return, a CTX-M group 1-producing E. coli, which displayed a different resistance pattern to that of the E. coli recovered at return, was also detected. Two months after return, a stool sample from traveller 1 was negative for MRE.Traveller 2 (C4-417)

A woman in her late twenties, travelled to northern India for 10 days in November 2012, with another person on a tour. She did not report any digestive disorders, any antibiotic intake or any contact with the local healthcare system during her travel. Direct cultures of stool samples collected at her return on agar media were negative, but cefotaxime enrichment broth yielded a CTX-M group 1-producing E. coli. Furthermore, the carbapenemase specific enrichment procedure used for this study yielded an OXA-181-producing E. coli. Traveller 2’s stool sample, originating from one month after return, was negative for any MRE carriage.Traveller 3 (C4-422)

A woman in her early thirties, travelled on her own to southern India for one month in January 2013, where she alternatively backpacked, participated in touristic tours and visited relatives living in India. At return, she reported having experienced digestive disorders, but she had not taken any antibiotics nor visited any healthcare centre during her journey in the country. From her stool sample at return, six phenotypically distinct E. coli were identified, among which one produced both CTX-M group 1 and New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM-1) carbapenemase. At months 1 and 2 after return, she was no longer carrying any CPE, but was still carrying one CTX-M group 1-producing E. coli. A stool sample from three months after return was negative for MRE.

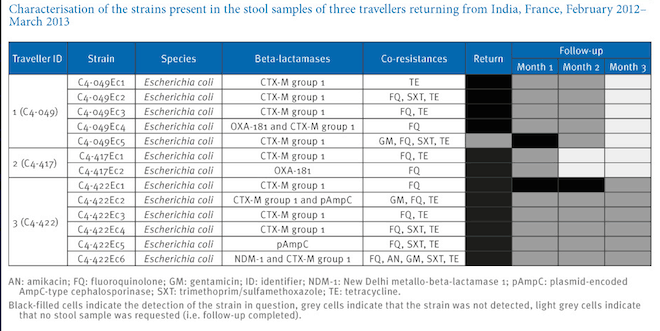

And for the microbio geeks among us, here’s what that resistance looked like:

Ruppe et al.; original here)

Why is this important? After all, probably anyone who travels anywhere interesting has had a bad bout of something gut-related at some point; we’re accustomed to the idea of picking up bacteria that cause “travelers’ diarrhea” and assume it is no big deal.

But it’s important because this is a big deal. These are bacteria so extremely resistant that, if they escaped the gut, they could cause a life-threatening untreatable infection. And “escaping the gut” is a very normal thing; that’s how people get urinary tract infections, and it’s how many hospital infections start.

The most troubling thing in this report is the authors’ sense that there’s no way for travelers to protect themselves against acquiring these bacteria. To protect Western hospitals, they suggest that anyone who has recently traveled to South Asia and needs health care when they return may have to be considered a contamination risk. That could mean just a flag in a medical chart, or it could mean isolation. Either way, it gives a whole new meaning to “adventure travel.”