image: NeilT (CC), Flickr

Happy new year, constant readers. Here’s the most urgent thing I have to say today: Stop reading and go set your DVRs for 8pm ET tonight. The fantastic The Poisoner’s Handbook, written by Wired colleague and dear friend Deborah Blum, has been adapted by PBS and airs tonight on The American Experience. It’s going to be superb.

Back? OK, on to business. Just before the holidays, the Food and Drug Administration finalized its long-aborning plan to ask the meat-production industry to reduce its use of routinely administered antibiotics. (My posts on the move here and here.) The FDA’s guidance to industry, as it is called, is not a regulation but rather a request for voluntary action on the part of veterinary-drug companies. It has met with skepticism and concerns that manufacturers will redefine the uses of their drugs in such a way that nothing will change.

The FDA action is aimed at the routine use of antibiotics for what is called growth promotion — causing animals to gain muscle faster than they would without the drugs being used — and is modeled on a ban on growth promoters enacted by the European Union in 2005. The goal, as in the EU, is to reduce the drugs’ use, and therefore the antibiotic-resistant bacteria that use stimulates.

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine, University of Calgary economist Aidan Hollis suggests though that a ban may not be the most useful or practical approach to the problem of drug overuse. In its place, he suggests the pocketbook persuasion of having to pay a fee.

Here are the criticisms.

- Bans are labor-intensive; to keep anyone from cheating, everyone has to be monitored.

- Ban are inefficient; they reduce all uses rather than the most problematic ones.

- Bans are costly: they raise the expense of meat production and also the price of retail meat — which regressively would fall hardest on farmers and consumers with the least resources.

And here are their (Hollis’s co-author is Ziana Ahmed of the University of Toronto) arguments on behalf of fees:

Every use of antibiotics increases selective pressure, thus undermining the value for other users. In effect, each antibiotic can have only a limited amount of use, so it is appropriate to charge a fee, just as logging companies pay “stumpage” fees and oil companies pay royalties. (A perfect fee would be calibrated to the extent of antibiotic resistance caused by each use; a practical fee, which is what we propose, would be based on the volume of antibiotics used.)

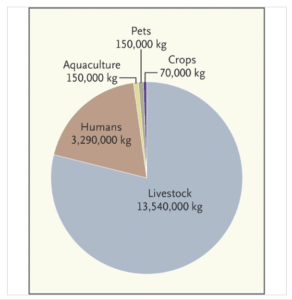

Estimated Annual Antibiotic Use in the United States. (shown as approximate numbers of kilograms of antibiotics used per year) via NEJM

Breaking that down:

- Fees are easy to administer (“at the manufacturing or importing stage”);

- Fees encourage producers to judge whether their actions, literally, justify their cost (“allow the farmer or veterinarian to decide whether the antibiotic confers enough benefits to make it worth the higher price”);

- Fees could be paid forward to drug-development or antibiotic-stewardship efforts (“help to restock and maintain the antibiotic cupboard”);

- And finally, fees could be coordinated between nations. (“…an even better approach would be an international treaty to recognize the fragility of our common antibiotic resources and to impose user fees to be collected by national governments… Such a treaty would also have a chance of attaining international compliance, since governments would be motivated to collect the revenues.”)

This isn’t the first time a user fee for antibiotics has been put forward; longtime readers may remember that the issue surfaced in spring 2011 during the observances for World Health Day. That proposal came from the Infectious Diseases Society of America — not an economists’ group, but a physicians’ association that has pressed for new incentives for drug development. At the time, one of their spokespeople compared a drug use-charge to the cost of the admission ticket for entering a national park — a fee paid to offset personal consumption of a jointly owned, over-used resource.

It’s common in journalism to look back, at the end of the year, and assess what were biggest or most persistent stories of the previous 12 months. While I didn’t perform that exercise, it’s clear to me that concern for antibiotic resistance, and especially the role played by agriculture in fomenting resistance, broke in 2013 from a niche concern among geeks like us into the mainstream.

With that as backdrop, I would expect the conversation in 2014 to move toward the practical realities of curbing antibiotic overuse while stimulating the production of badly needed new drugs. Exploration of incentives — and disincentives — will be an important part of that discussion, and this paper can serve as a much-needed start.

Cite: Holis A, Ahmed Z. Preserving Antibiotics, Rationally. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:2474-2476. December 26, 2013. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1311479