image: NeilT (CC), Flickr

Happy new year, constant readers. Here’s the most urgent thing I have to say today: Stop reading and go set your DVRs for 8pm ET tonight. The fantastic The Poisoner’s Handbook, written by Wired colleague and dear friend Deborah Blum, has been adapted by PBS and airs tonight on The American Experience. It’s going to be superb.

Back? OK, on to business. Just before the holidays, the Food and Drug Administration finalized its long-aborning plan to ask the meat-production industry to reduce its use of routinely administered antibiotics. (My posts on the move here and here.) The FDA’s guidance to industry, as it is called, is not a regulation but rather a request for voluntary action on the part of veterinary-drug companies. It has met with skepticism and concerns that manufacturers will redefine the uses of their drugs in such a way that nothing will change.

The FDA action is aimed at the routine use of antibiotics for what is called growth promotion — causing animals to gain muscle faster than they would without the drugs being used — and is modeled on a ban on growth promoters enacted by the European Union in 2005. The goal, as in the EU, is to reduce the drugs’ use, and therefore the antibiotic-resistant bacteria that use stimulates.

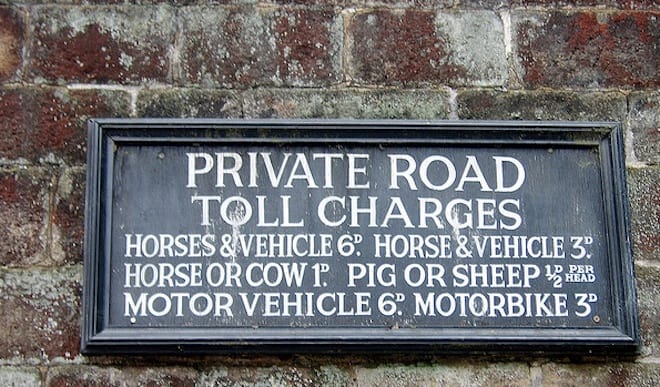

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine, University of Calgary economist Aidan Hollis suggests though that a ban may not be the most useful or practical approach to the problem of drug overuse. In its place, he suggests the pocketbook persuasion of having to pay a fee.