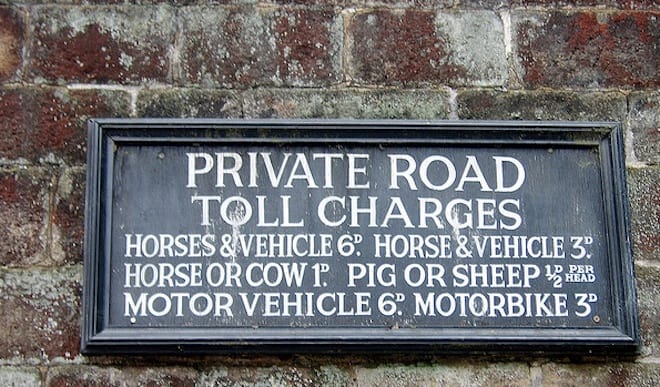

Image: Zach Bulick/Flickr

Double-barreled news today from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In an analysis of several sets of hospital data, gathered by the agency and also purchased from independent databases, the CDC said it found that more than 37 percent of prescriptions written in hospitals involved some sort of error or poor practice, increasing the risk of serious infections or antibiotic resistance. And in a surprise announcement timed to the release of the federal draft budget, the agency said it is in line to receive $30 million to enhance its work combating antibiotic resistance in the US.